Why the Basque country?

I was asked variations of this question when I explained that I would be away from my two schools for a week in January to visit the Basque country with the Leadership Academy. My staff and governors asked, ‘why go to the Basque country?’ The pupils in assembly wanted to know ‘what’s in the Basque country?’ and I have to admit I found myself asking ‘where exactly is the Basque country?!’ Being a place, I knew very little about I logged on to my Mac to do some quick research.

The headlines

- The Basque government has invested heavily in education. If the Basque region were ranked as a country, only Denmark and Austria would have higher levels of per-pupil spending in Europe.

- About half of the Basque schools are a mixture of public and private, where the state pays most of the funding, but parents are also expected to contribute.

- The Basque government’s education minister says the commitment to education is strongly linked to national identity. “Education is the key to keeping our culture,” she says.

And for those of you like me wondering where exactly the Basque country is… here’s the map.

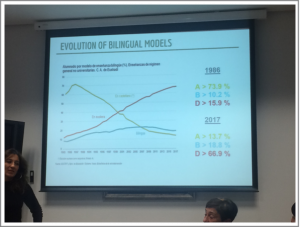

Government graphs

Ten hours after touching down in Bilbao myself and my fellow associates found ourselves deep inside the labyrinth that serves as the city council offices. Not long into our welcome from the director the impact of policy on the Basque language in particular was encouraging.

Offering three language models; A Spanish delivery with minimal Basque; B 50:50 Spanish: Basque and D (quick fact: there is no letter ‘C’ in Basque) Basque delivery with minimal Spanish. The region had seen a dramatic cultural shift over a thirty-year period from parents selecting model D schools from 15.9% in 1986 to 66.9% by 2017.

So how did they do it?

I’ve listed below the standout points for me, in only a short blog it is impossible to list everything learnt from the trip however, it goes without saying that a lot of initiatives discussed with us were only possible with government funding.

- An early strategic plan for the deployment of teachers who spoke Basque to ensure they went to teach in provinces where the speaking of Basque was poor.

- Two-year full time sabbatical language training for all teachers.

- A dedicated government programme to promote the Basquisation of school atmosphere (NOLEGA) which includes short stay residential centres; grants to schools to promote theatre, the performance of sung verse in the traditional style; exchanges between schools from different sociolinguistic areas aimed at increasing the use of Basque among pupils and annual prize contests for prose, poetry and elocution.

But what do the kids say?

At this point the similarities (and problems) of Wales and the Basque country started to show. We were fortunate to visit five schools in the Basque country ranging from public to private and junior to senior with all providing language model D to their communities. When faced with two simple questions nearly all children gave the same answer:

“Do you speak Basque at home?” Overwhelmingly the answer to this question was “no” with Spanish being the preferred language to use with family and friends.

However, following this question with “are you Basque or are you Spanish?” An equally overwhelming answer was given… “we are Basque!”

Which brings us to a key factor to consider, that language competence does not ensure language use. And language use depends on other factors, in particular on public demand. Without native parents using the language at home, the school can at best and at great cost produce competent second language speakers, who are secondary for the survival of the Basque language.

Final words

The 1978 Spanish constitution declared that Spaniards had a duty to know Spanish. But it also added that each regional community could declare its local language official, thus implying the right of those communities to regulate its use. It goes without saying that the Basque autonomous region has taken this right and delivered, transforming the language competence of its’ workforce and being responsible for a cultural shift in its’ citizens to embrace the Basque language and heritage.

All this work has been achieved by a generation which suffered an oppression of their language and culture during a Francoist Spain. It remains to be seen whether this next generation will be quite as militant in the pursuit of its own language rights. Will they share their parents’ enthusiasm for their mother tongue, or will their identity be more in line with a global community in an ever shrinking world?

We used a lot of public transport during our visit, I took this photo on my first day in the Basque country but the sight was not uncommon. A group of teenagers studying on their way to school. It reminded me of the American philosopher John Dewey who said “The most important attitude that can be found is the desire to go on learning.” The Basque country students I saw certainly embodied this attitude as did the professionals we met with who were keen to learn from the good practice taking place in Wales. As an associate for the National Academy I hope to also take the lessons learnt from the Basque educational system to help inform our own thinking.

Richard Monteiro – Headteacher of The Federation of Ysgol Bryn Clwyd and Ysgol Gellifor